ε-quadratic form

In mathematics, specifically the theory of quadratic forms, an ε-quadratic form is a generalization of quadratic forms to skew-symmetric settings and to *-rings;  , accordingly for symmetric or skew-symmetric. They are also called

, accordingly for symmetric or skew-symmetric. They are also called  -quadratic forms, particularly in the context of surgery theory.

-quadratic forms, particularly in the context of surgery theory.

There is the related notion of ε-symmetric forms, which generalizes symmetric forms, skew-symmetric forms (= symplectic forms), Hermitian forms, and skew-Hermitian forms. More briefly, one may refer to quadratic, skew-quadratic, symmetric, and skew-symmetric forms, where "skew" means  and the * (involution) is implied.

and the * (involution) is implied.

The theory is 2-local: away from 2, ε-quadratic forms are equivalent to ε-symmetric forms: half the symmetrization map (below) gives an explicit isomorphism.

Contents |

Definition

ε-symmetric forms and ε-quadratic forms are defined as follows.[1]

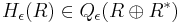

Given a module  over a *-ring

over a *-ring  , let

, let  be the space of bilinear forms on

be the space of bilinear forms on  , and let

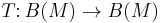

, and let  be the "conjugate transpose" involution

be the "conjugate transpose" involution  . Let

. Let  ; then

; then  is also an involution. Define the ε-symmetric forms as the invariants of

is also an involution. Define the ε-symmetric forms as the invariants of  , and the ε-quadratic forms are the coinvariants.

, and the ε-quadratic forms are the coinvariants.

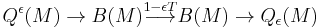

As a short exact sequence,

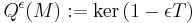

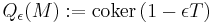

As kernel (algebra) and cokernel,

The notation  follows the standard notation

follows the standard notation  for the invariants and coinvariants for a group action, here of the order 2 group (an involution).

for the invariants and coinvariants for a group action, here of the order 2 group (an involution).

We obtain a homomorphism  which is bijective if 2 is invertible in R. (The inverse is given by multiplication with 1/2.)

which is bijective if 2 is invertible in R. (The inverse is given by multiplication with 1/2.)

An ε-quadratic form  is called non-degenerate if the associated ε-symmetric form

is called non-degenerate if the associated ε-symmetric form  is non-degenerate.

is non-degenerate.

Generalization from *

If the * is trivial, then  , and "away from 2" means that 2 is invertible:

, and "away from 2" means that 2 is invertible:  .

.

More generally, one can take for  any element such that

any element such that  .

. always satisfy this, but so does any element of norm 1, such as complex numbers of unit norm.

always satisfy this, but so does any element of norm 1, such as complex numbers of unit norm.

Similarly, in the presence of a non-trivial *, ε-symmetric forms are equivalent to ε-quadratic forms if there is an element  such that

such that  . If * is trivial, this is equivalent to

. If * is trivial, this is equivalent to  or

or  .

.

For instance, in the ring ![R=\mathbf{Z}\left[\textstyle{\frac{1%2Bi}{2}}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a8d54b6276863f24de721f8fa9c8b6d3.png) (the integral lattice for the quadratic form

(the integral lattice for the quadratic form  ), with complex conjugation,

), with complex conjugation,  is such an element, though

is such an element, though  .

.

Intuition

In terms of matrices, (we take  to be 2-dimensional):

to be 2-dimensional):

- matrices

correspond to bilinear forms

correspond to bilinear forms - the subspace of symmetric matrices

correspond to symmetric forms

correspond to symmetric forms - the subspace of (-1)-symmetric matrices

correspond to symplectic forms

correspond to symplectic forms - the bilinear form

yields the quadratic form

yields the quadratic form

-

,

,

- which is a quotient map with kernel

.

.

Refinements

An intuitive way to understand an ε-quadratic form is to think of it as a quadratic refinement of its associated ε-symmetric form.

For instance, in defining a Clifford algebra over a general field or ring, one quotients the tensor algebra by relations coming from the symmetric form and the quadratic form:  and

and  . If 2 is invertible, this second relation follows from the first (as the quadratic form can be recovered from the associated bilinear form), but at 2 this additional refinement is necessary.

. If 2 is invertible, this second relation follows from the first (as the quadratic form can be recovered from the associated bilinear form), but at 2 this additional refinement is necessary.

Examples

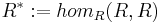

An easy example for an ε-quadratic form is the standard hyperbolic ε-quadratic form  . (Here,

. (Here,  denotes the dual of the

denotes the dual of the  -module

-module  .) It is given by the bilinear form

.) It is given by the bilinear form  . The standard hyperbolic ε-quadratic form is needed for the definition of L-theory.

. The standard hyperbolic ε-quadratic form is needed for the definition of L-theory.

For the field of two elements  there is no difference between (+1)-quadratic and (-1)-quadratic forms, which are just called quadratic forms. The Arf invariant of a nonsingular quadratic form over

there is no difference between (+1)-quadratic and (-1)-quadratic forms, which are just called quadratic forms. The Arf invariant of a nonsingular quadratic form over  is an

is an  -valued invariant with important applications in both algebra and topology.

-valued invariant with important applications in both algebra and topology.

Given an oriented surface  embedded in

embedded in  , the middle homology group

, the middle homology group  carries not only a skew-symmetric form (via intersection), but also a skew-quadratic form, which can be seen as a quadratic refinement, via self-linking. The skew-symmetric form is an invariant of the surface

carries not only a skew-symmetric form (via intersection), but also a skew-quadratic form, which can be seen as a quadratic refinement, via self-linking. The skew-symmetric form is an invariant of the surface  , whereas the skew-quadratic form is an invariant of the embedding

, whereas the skew-quadratic form is an invariant of the embedding  , e.g. for the Seifert surface of a knot. The Arf invariant of the skew-quadratic form is a framed cobordism invariant generating the first stable homotopy group

, e.g. for the Seifert surface of a knot. The Arf invariant of the skew-quadratic form is a framed cobordism invariant generating the first stable homotopy group  .

.

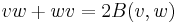

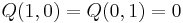

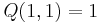

For the standard embedded torus, the skew-symmetric form is given by  (with respect to the standard symplectic basis), and the skew-quadratic refinement is given by

(with respect to the standard symplectic basis), and the skew-quadratic refinement is given by  with respect to this basis:

with respect to this basis:  : the basis curves don't self-link; and

: the basis curves don't self-link; and  : a (1,1) self-links, as in the Hopf fibration. (This form has Arf invariant 0, and thus this embedded torus has Kervaire invariant 0.)

: a (1,1) self-links, as in the Hopf fibration. (This form has Arf invariant 0, and thus this embedded torus has Kervaire invariant 0.)

Applications

A key application is in algebraic surgery theory, where even L-groups are defined as Witt groups of ε-quadratic forms, by C.T.C.Wall

References

- ^ Foundations of algebraic surgery, by Andrew Ranicki, p. 6